Natural hair movement: Emma Dabiri on the afro hair revolution that’s finally taking root

By . - Tuesday, May 28, 2019

Don’t Touch My Hair author and historian Emma Dabiri went from enduring her hair, to enjoying it, to truly loving it, and hopes that natural afro hair is finally growing away from its undeserved history of shame and stigma

I always wanted straight hair. In fact, ‘wanted’ doesn’t adequately capture the depth of the desire. Let’s say I would have killed for straight hair. Prayers and curses were offered when, as a teenager, I desperately implored my tightly coiled kinks to transform into something resembling the glossy locks that flowed over the shoulders of everyone else around me.

Growing up in Ireland in the Eighties was characterised for me by racism, isolation, bullying and stigmatisation. My hair in particular seemed to be a spectacle, the site where most of this attention was concentrated. It was a constant source of deep, deep shame, an emotion that went far beyond embarrassment. Racism formed the backbone of my day-to-day experiences. I was the “black one”, the “dark one”, and these were the more polite epithets. But polite or not – usually not – it was constant.

Many of us are preoccupied with looking good. But for black women, it’s about looking ‘normal’, about assimilating into a frequently hostile environment. It’s about not looking ‘threatening’ or ‘wild’. Not being dubbed the ‘scary’ one of the Spice Girls.

But slowly change has started to take effect, mostly thanks to the natural hair movement that started in the United States. ‘Naturals’ are people who have decided to stop relaxing their hair and embrace its unaltered texture, which includes styles such as twists, braids and dreadlocks.

It began as a community comprised of bloggers, YouTubers and forum users, all looking for and offering support as they moved away from chemical relaxers. Some would become popular enough to appear at events dedicated solely to natural hair, attracting crowds of thousands, mostly young women.

The Curly Girl Collective are champions of natural hair (even their systems analyst is a woman with incredible curls). Their first CurlFest was held in 2014 in Brooklyn, New York, and 1,000 people attended. The event now attracts 35,000 every year. In 2017, the Natural Hair Academy in Paris held what was described as the biggest natural hair event in the world. In South Africa last year, 25 years after the end of apartheid, natural hair events were promoted by the country’s largest chain of chemists, Clicks.

I first became aware of this nascent revolution when it was just a few years old, but even before I did, I was starting to feel my relaxing days were numbered. I had started to examine why I felt so bad about my hair.

For black women – particularly those of us with tighter, kinkier hair textures – there was a system that placed us outside the boundaries of femininity, even outside humanity itself. The long years of slavery (which lasted from the 17th century up until 1888 in Brazil, the last country in the western hemisphere to abolish it) bequeathed most of our ideas about what we now understand as the ‘white race’ and the ‘black race’.

The idea that these two groups of people were distinct ‘races’ with hereditary character traits was required. It was a way of justifying the barbaric enslavement of millions of black and mixedrace people; people whose unremunerated labour formed the foundation on which western Europe and the US built their modern economies.

Hair was one of the primary features used to distinguish black from white. What was more self-evident of the distance between us and a European standard of humanity than the “wool” that grew from our heads, said to be more similar to that of animals?

For some slave masters, this distinction was insisted upon, particularly where the appearance of their slaves’ hair differed little from their own. One account, from Shane White and Graham White’s Slave Hair And African American Culture In The Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries, tells us: “Mistress Uster ask me what that was I had on my head and I would tell her, ‘Hair,’ and she said, ‘No, that ain’t hair, that’s wool.’ [But] I had straight hair and my mistress would say, ‘Don’t say hair, say wool’.”

All change

Of course, I wasn’t privy to all this context as a child. I just knew that I hated my hair. And so did everybody else. My mother is white and Irish, my father is black and Nigerian.

My hair texture favours the Nigerian side of my heritage. Rather than the type of texture commonly assumed to be possessed by people of mixed race, my hair is not curly, it is not in ringlets. It does not grow down towards the ground. Rather, it is tightly coiled, colloquially referred to as ‘kinky’. It grows up and out. The words used to describe it in English are ‘coarse’ and ‘tough’, ‘unmanageable’ and ‘defiant’. It is seen as deviant, hair that needs to be brought under control.

The unique texture of afro hair, its tightly spiralled coils, makes it possible to style in a multitude of ways that are hard, if not impossible, to achieve with European hair. Its structure also means that leaving it ‘out’ for too long means it becomes dry and tangled – which is part of the rationale behind twists and braids, the protective styles black women often sport.

In black cultures, it is entirely ordinary for women to change their hairstyle with what seems to many white observers as confusing frequency. Change is a constant, so mixing it up with weaves, wigs and extensions is a cultural norm.

But even given the vast variety of styles that are commonplace in the western world, it is worthy of note that throughout the 20th century and until very recently, very few worked with afro hair texture. I took this on too: when I was younger I was always trying to get as far away from my own texture as possible by relaxing it.

But something didn’t sit right. I could never really reconcile my increasing awareness, my politics, my world view, with what I was doing to my hair. But to stop, to go natural, was unthinkable. I’d spent my whole life running away from it, determined to disguise it by any means necessary. I had to undo a lot of social conditioning and it wasn’t a short process. It was only when I reached my early 30s that I had the confidence and selfpossession to make the change; to embrace my natural hair.

Everybody’s natural hair story is different. Many women are adamant that their decision to stop relaxing their hair was not a political one. There are links between cancer, fertility issues, fibroids and the chemicals in straightening creams. Salon time is lengthy and costly. Relaxing can hurt your hair and your head. But my decision was political. I emphatically did not want afro-textured hair, yet I could no longer reconcile my politics with chemically straightening it.

Around 2010, I became aware of a website called Black Girl with Long Hair (BGLH) founded by blogger Leila Noelliste. That was the first time I really saw my hair texture celebrated – not only shiny, glossy curls but the matte, springy naps that can be twisted, stretched, coiled and curled into any and every shape imaginable.

As the name of the blog suggests, our hair can grow – one of the negative qualities attributed to afro hair is that it doesn’t. In fact, more often than not, limited growth is the result of damaging practices or lack of knowledge. Now, I was presented with all these beautiful sisters rocking very cool, very chic, often alternative looks with their very own natural hair. And if they could do it, so could I. Couldn’t I?

New growth

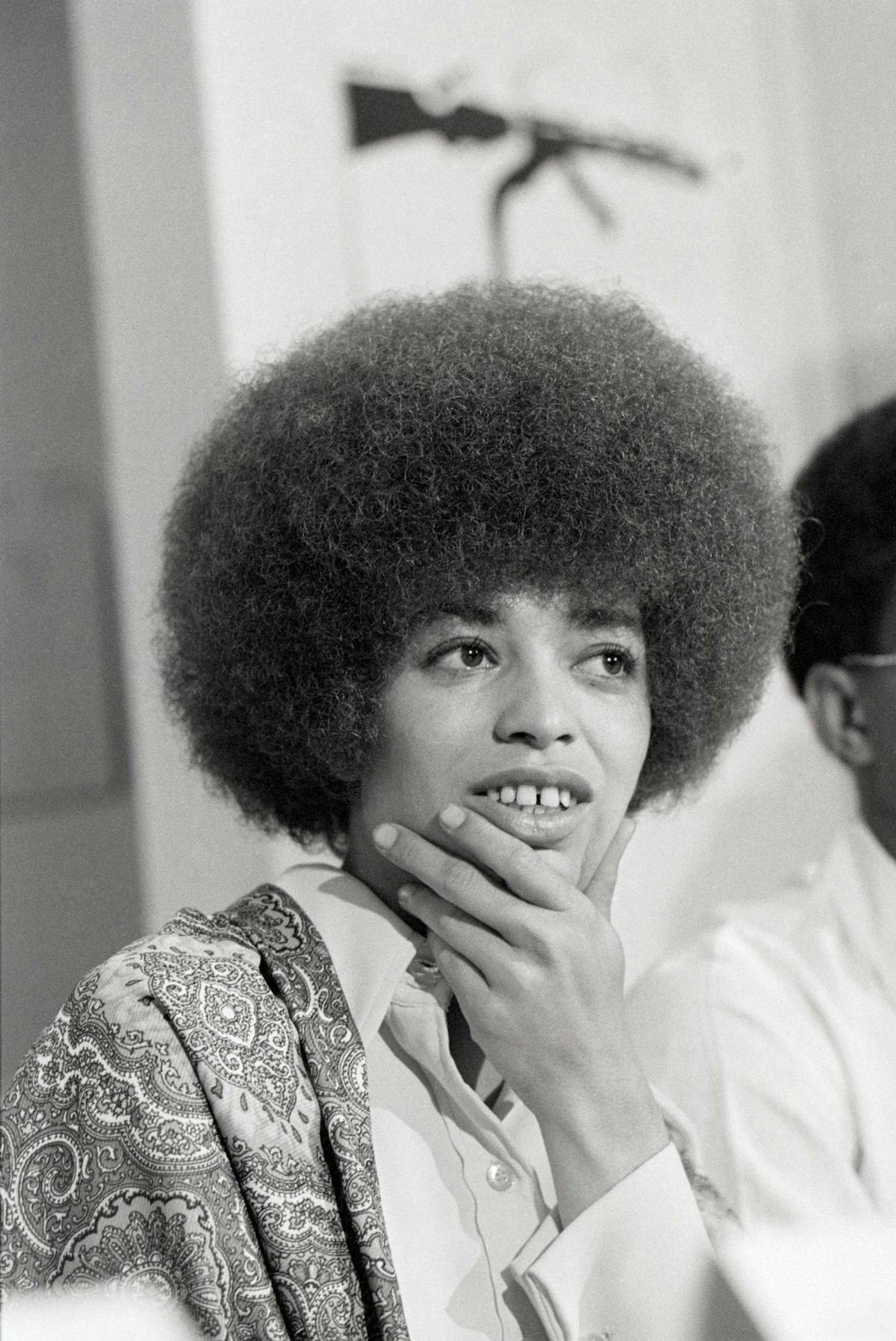

Natural hair has had moments in the sun before. In the Sixties, activists – most prominently Angela Davis and the Black Panther women – made the Afro famous. This was about rejecting western beauty standards and the need to conform, but also acted as a challenge to consumer culture, as many women started to forgo expensive treatments at salons.

But it didn’t last: by the Eighties and throughout the Nineties and even beyond, straightness was once again the default for most black women.

This all meant, at 30 years old, that I did not know my own hair. I was not familiar with its natural appearance, nor was I remotely in tune with its requirements. Once you chemically straighten your hair, you can’t un-straighten it. It’s an irreversible process. The only option is the ‘big chop’, a term used within the natural hair community to describe cutting off the relaxed or permed ends when you transition from chemically processed to natural hair.

But I wasn’t ready for short hair – I stopped relaxing it and let the roots grow out so that when I eventually cut it there would be some length. Now I wish I’d been more daring, rocked a TWA (teeny weeny afro) or just shaved it all off, but, in all honesty, I was still too traumatised by the attitudes I’d faced during my childhood. At 31, I became pregnant, and, finally… CHOP.

There were a lot of motivations. They say your hair grows quickly while you’re pregnant, but it was more than that. I knew that if I had a daughter, it was important to me that she did not grow up with the same distorted concept of beauty I’d held. Moreover, if I was having a boy, such enlightenment was just as crucial, if not more so.

The energy around me shifted. I moved away from enduring my hair to actively enjoying it and eventually loving it. This new mindset has corresponded with huge changes in my life – not just becoming a mother, but also the most contented, fulfilling and creative years I’ve known.

Many African cultures believe our hair is of profound spiritual significance. It’s hard not to wonder whether my hair’s newfound freedom – its irrepressible volume and height – has helped me to access those spiritual dimensions I’d previously been smothering with chemicals.

The current natural hair movement is not as explicitly political or anti-consumerist as its Sixties predecessor. But it is bigger. The landscape is different now, different to how it was even at the start of this decade. In 2019, un-relaxed hair is on more heads, in more places. It has grown far larger than people who would consider themselves members of the natural hair community (‘naturalistas’ as we’re often called), and, in many places, it’s happily becoming another norm. The mainstream has finally taken note.

Think of recent films. The huge variety of twists and braids on the women in last year’s superhero smash Black Panther. Lupita Nyong’o runs for her life in the terrifying Us and just happens to have hair that coils like mine. There’s Yara Shahidi in Black-ish and Grown-ish. There’s Viola Davis on every red carpet, jazz musician Esperanza Spalding, Emmanuel Macron’s right-hand woman Sibeth Ndiaye. This spring, fashion weeks in New York, London, Milan and Paris all featured models with natural afro hair.

It’s a start, but it’s not everything. We need to work to ensure this representation isn’t just fleeting or tokenistic, that the wheel of fashion doesn’t spin again and undo all of our gains. This is our hair. It’s not just another trend. It’s who we are.

0 comments

Leave a comment and show some love!